Planet Hunters

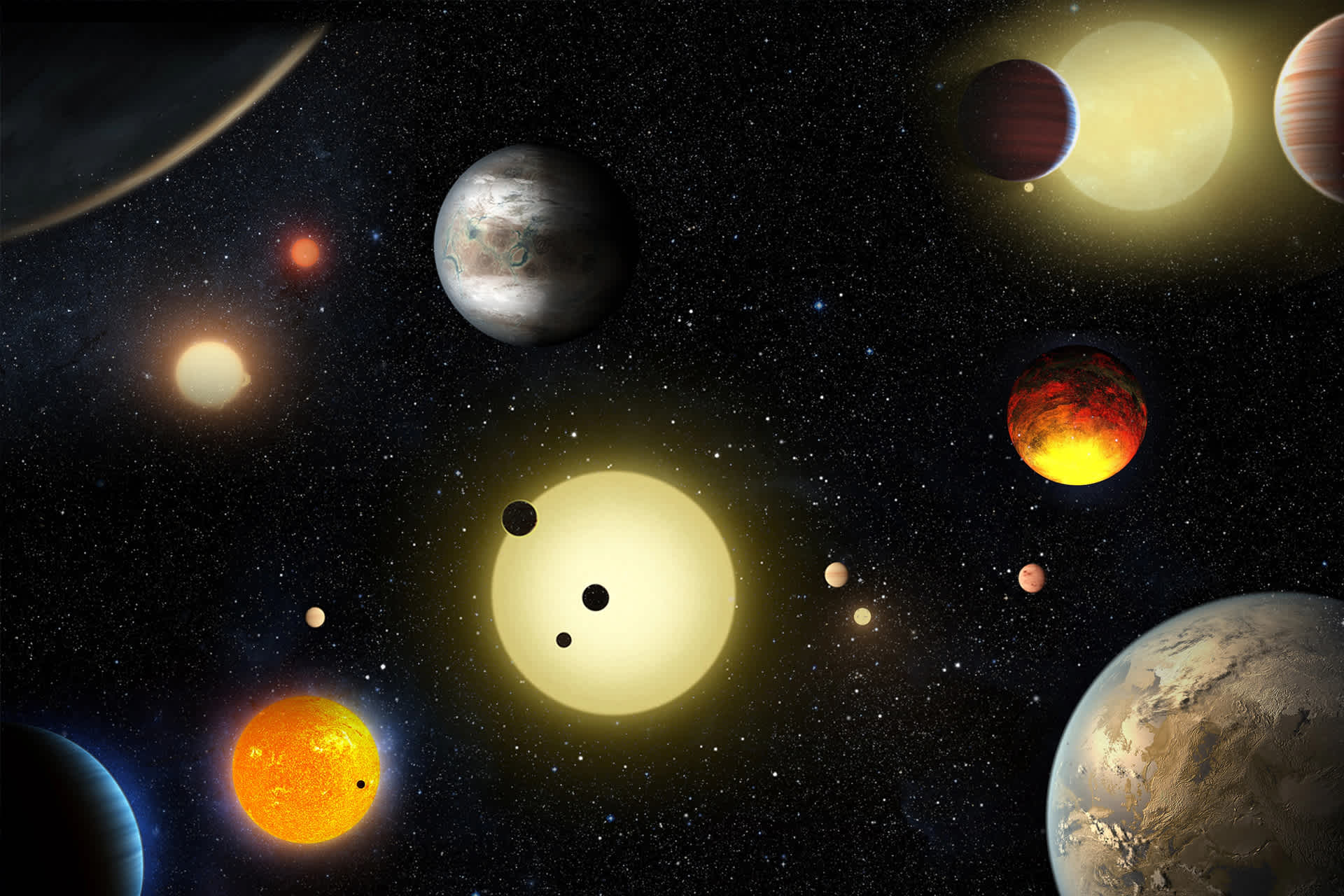

There may be no new planets to discover close to Earth. However, across the rest of the galaxy, the planet-hunting business is booming. According to findings NASA announced on May 10, 2016, astronomers working with the Kepler Space Telescope have added 1,284 new exoplanets to the roster of known worlds orbiting stars other than our sun. That’s on top of 984 other exoplanets already confirmed, as well as 1,327 others that are considered likely.

Most important, of the newly confirmed planets, nine qualify as the most sought-after type of all: ones less than twice the size of Earth—which means they likely have solid surfaces—orbiting their stars in the so-called Goldilocks zone. That’s where the temperature stays within the not-too-hot, not-cold-cold range for liquid water to exist. If life as we know it is going to emerge anywhere in space, planets like that are the first place to look.

The 1,284 exoplanets were discovered by a combination of optics and arithmetic. The Kepler telescope, which was launched in 2009 and retired in 2018, searched for planets by staring unblinkingly at 150,000 stars—a tiny sampling of the 300 billion or so in the Milky Way. It was looking for the slight dimming of light that occurs when an orbiting planet crosses a star’s face.

That method, however, can yield false positives. “There are a lot of scenarios that mimic the transiting planet signal,” said Princeton astronomer and Kepler researcher Timothy Morton in a press conference.

Eliminating the impostors can be slow and painstaking. Morton has streamlined this process with a computer model. It factors together the strength of the transiting signal, the size and color of the star, and more. Taken together, these x-factors can determine the likelihood that a possible planet is a real planet to within a certainty of 99%. Only the ones that meet or exceed that threshold make the confirmation cut—as the 1,284 announced did.

“Kepler is interested in statistics,” said Natalie Batalha, Kepler mission scientist at NASA’s Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, California. “We are searching the galaxy to see how far we have to look to find potentially habitable planets.”

Follow-on telescopes including the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) and the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) will look for those and other worlds. Webb particularly may be able to analyze the atmosphere of any earth-like planets that have them. It may look for telltale signs of life like water, methane, and carbon dioxide.

Humanity’s great cosmic mystery—whether we’re alone in the universe—is still unresolved. But what the 1,284 planets make clear is that there are surely plenty of worlds out there where life as we know it could find a comfortable home.

This story was originally published in TIME on May 10, 2016.