The Future of Zoos

Can zoos meet the needs of animals? Should zoos exist?

For kids at the Philadelphia Zoo, in Pennsylvania, it was a close encounter of the ferocious kind. Directly in front of them was a Siberian tiger. But the kids did not panic. They laughed. The tiger was inside an enclosed path.

At the Philadelphia Zoo’s Big Cat Crossing, tigers can follow their instinct to watch over their turf.

That tiger trail is part of Zoo360. The exhibit has changed the way humans and animals experience the zoo. But Zoo360’s bigger impact may be how it treats its animals.

Lions look down on zoo visitors.

PHILADELPHIA ZOOMany experts think zoos need to change if they’re going to last. The Philadelphia Zoo is a good model for that.

Studies show that many animal species are smarter and feel more than we have understood. Animals may suffer when they are removed from the wild. If so, should they be held in captivity?

“Even the best zoos today are based on captivity,” says Jon Coe. He is the designer who invented the Zoo360 idea. “To me, that’s the fundamental flaw.”

In 1975, David Hancocks became the director of the Woodland Park Zoo, in Seattle, Washington. He hired Coe and asked him to rethink how zoo animals are kept. Coe developed a plan that combined natural vegetation

vegetation

WITOLD SKRYPCZAK—LONELY PLANET IMAGES/GETTY IMAGES

plants

( )

A cactus is a form of vegetation found in a desert

, plenty of room, and lots of light.

WITOLD SKRYPCZAK—LONELY PLANET IMAGES/GETTY IMAGES

plants

( )

A cactus is a form of vegetation found in a desert

, plenty of room, and lots of light.

Creature Connection

The new polar-bear exhibit at the St. Louis Zoo, in Missouri, also has animals’ best interests at heart. The enclosure takes up 40,000 square feet. It has an area for each of the polar bear’s environments: sea, coast, and tundra

tundra

MICHAEL DEYOUNG—GETTY IMAGES

a vast, treeless, arctic region

( )

The tourists hiked across the Alaskan tundra.

.

MICHAEL DEYOUNG—GETTY IMAGES

a vast, treeless, arctic region

( )

The tourists hiked across the Alaskan tundra.

.

A white-handed gibbon at the Philadelphia Zoo has room to explore.

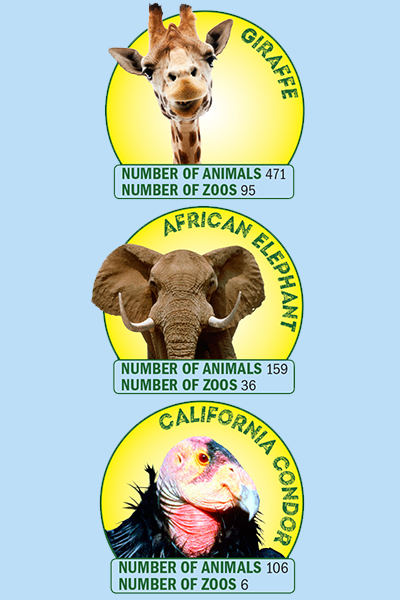

FRANCK BOHBOT FOR TIMEBut many zoos do not have the money and space needed to provide proper habitats. Elephants, for example, need company. In 2011, the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) started requiring zoos with elephants to keep at least three. Not every zoo can afford to do that.

Hancocks has done a lot to shape the zoos we see today. Now he spends more time thinking about their problems and future. An exhibit might look better than a cage, but is the exhibit good for the animal? “A concrete tree is as useless as a light pole,” he says. “From the animals’ point of view, they’re really no better off.”

Most zoo officials don’t agree. Many have dedicated their lives to working with animals. Ask a dozen zoo directors why these places should exist today, and education, conservation, and science all come up. But helping people understand animals is the most common answer.

More people than ever are going to zoos. According to the AZA, in 2015, U.S. zoos had more than 170 million visitors. Still, those big numbers will do little to lessen the growing arguments against keeping animals captive.

“Where are we going?” asks David Towne, who once oversaw the Woodland Park Zoo. “I guess I’m worried.”