Shark Hunt

A shark smells prey and swims toward it. The meal is some bait attached to a camera on the ocean floor. The big fish heads to the camera, and it is caught on video. The scene is not for a movie or TV show. It is for Global FinPrint, a project to create the first worldwide census of sharks.

The three-year project began in June. It also focuses on rays. Both sea creatures face challenges to their survival. A main goal of Global FinPrint is to find out where sharks and rays need help the most.

In waters near the Bahamas, a reef shark swims with other fish near a coral reef.

COURTESY GLOBAL FINPRINT“Sharks and rays are under threat from fishing, habitat loss, and climate change,” Demian Chapman told TFK. He is a marine biologist at Stony Brook University, in New York, and the lead scientist for the project. The team includes researchers in the United States and Australia.

Finding the Hot Spots

Millions of sharks and rays are killed each year. According to a 2013 study, around 100 million sharks are killed yearly. The fish are hunted for their meat and fins. In parts of Asia, the fins are prized for use in shark-fin soup.

A whitetip reef shark swims abovea shallow a coral reef in the South Pacific, off the coast of Fiji.

TOBIAS BERNHARD RAFF—MINDEN PICTURESScientists want to learn more about the areas where sharks are doing well. “We want to find the hot spots, the places that still have lots of sharks and rays, and determine what makes them hot spots,” Chapman says. Researchers will compare information from hot spots with data from areas where there are few sharks and rays or where the number of the fish is unknown.

A Global FinPrint researcher swims close to a tiger shark.

COURTESY GLOBAL FINPRINTUnderwater cameras play a key role in the project. Scientists study the video and note when and where a shark or ray appears. To make sure they don’t count the same fish more than once, scientists record its size, species, and markings. “We add all this information to the database,” Chapman says.

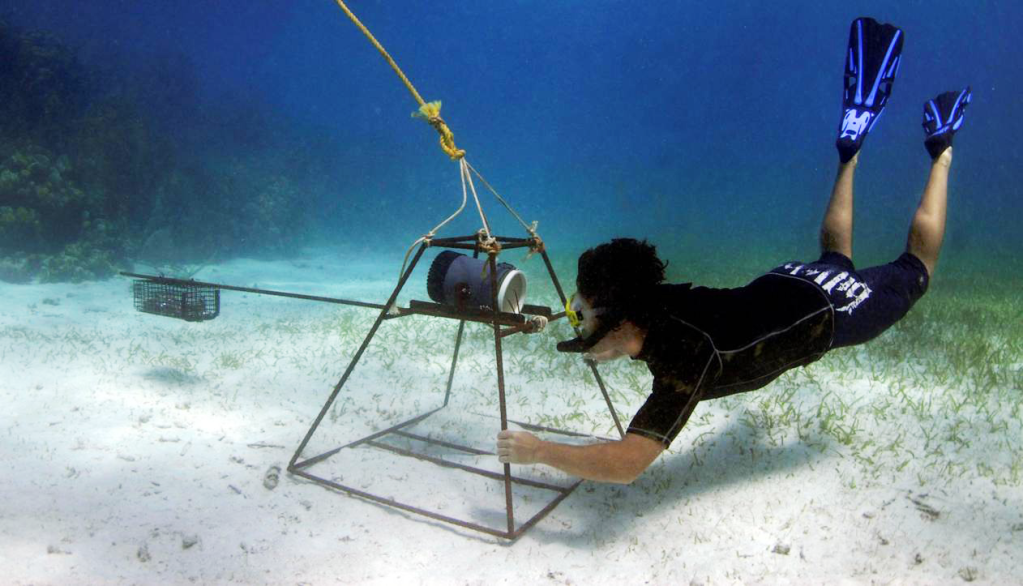

Bait on this underwater camera will attract sharks.

COURTESY GLOBAL FINPRINTGlobal FinPrint will be finished in 2018. Chapman says the information in the census will be useful to governments and organizations that want to protect the fish. “It will help determine what conservation efforts are needed around the world,” he says, “and how to choose areas for protection.”

Water Safety

Shark attacks in U.S. waters left beachgoers nervous this summer. But experts say shark attacks are rare. According to new a study, in California, it is 91% less likely that a shark will attack a human today than it was in the 1950s.

The study says that in 2013, there was one shark attack for every 738 million beach visits by swimmers in California. “You have more of a chance to win the lottery than being bitten by a shark,” says scientist Francesco Ferretti. He led the study.

THINK! How will counting sharks help scientists protect them?