Twice a week, Adam Knox jumps into a pickup truck. He drives to a forest high in the Hawaiian mountains. “You feel like you’re in Jumanji, or one of those adventure-type movies,” Knox tells TIME for Kids. “This is where the native birds live.”

He’s talking about honeycreepers. They’re in danger of going extinct extinct no longer existing (adjective) because of avian malaria. That’s a disease spread to birds by mosquitoes. Knox is a drone pilot for the American Bird Conservancy (ABC). He goes into the forest to release more mosquitoes.

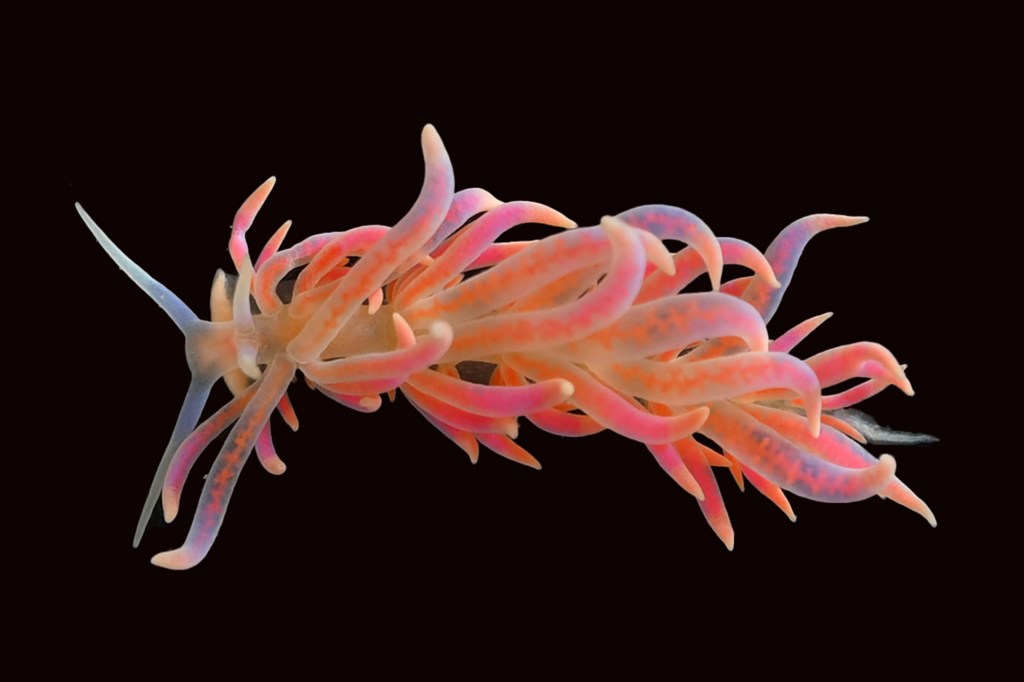

SPOTTED! A scarlet honeycreeper, once common in Hawaii, is now a rarer sight.

ROBBY KOHLEY

That may sound strange, but it’s cutting edge. “This technique uses mosquitoes to fight mosquitoes,” says scientist Christa Seidl. She works for the Maui Forest Bird Recovery Project. The group, along with ABC, is joining forces with others to save honeycreepers. (See “Working Together.”)

The mosquito project began in 2023. Insects were delivered by helicopter then. Now, mosquitoes go to the forest by drone. “It’s been a long road to get here, with a lot of trial and testing,” Knox says. Drones are quieter. They cost less. They allow for more-flexible timing. Since April, Knox has been using drone technology to help drop half a million mosquitoes a week.

READY TO FLY Drone pilot Adam Knox prepares to send a drone over the forest to release mosquitoes earlier this year.

AMERICAN BIRD CONSERVANCY

Innovation at Work

Honeycreepers live only in Hawaii. There used to be more than 50 types. “Now there are only 17,” says Chris Farmer, ABC’s Hawaii program director.

Mosquitoes are not native to Hawaii. And they are not good neighbors. A single mosquito bite can kill a honeycreeper.

YELLOW FLASH A Maui parrotbill is a type of honeycreeper named for its parrotlike beak.

ROBBY KOHLEY

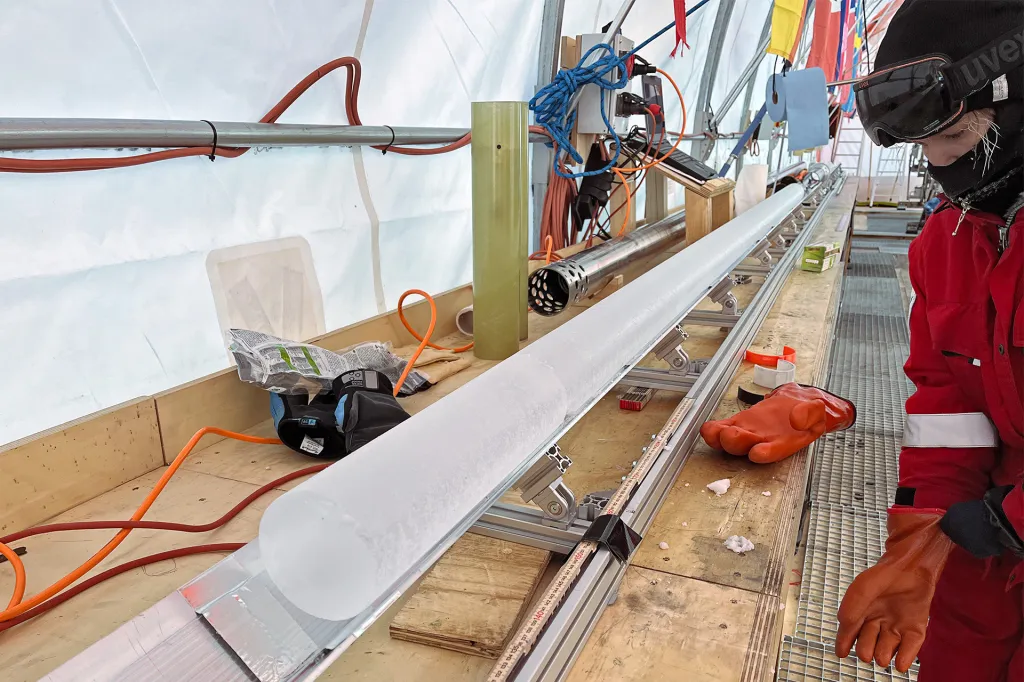

The mosquitoes Knox drops into the forest are in biodegradable biodegradable capable of being broken down naturally (adjective) pods. Each holds 1,000 insects. The mosquitoes are males. They don’t bite or transmit disease. Pods are loaded into the drone at the launch site. After liftoff, Knox releases them by remote control.

DROP DOWN A pod of about 1,000 mosquitoes is dropped into a Hawaiian forest by drone.

ADAM KNOX—AMERICAN BIRD CONSERVANCY

The dropped mosquitoes are bred in a lab. When they mate with wild ones, the eggs won’t hatch. “This lowers the mosquito population over time,” Seidl says, especially since most females mate only once. It also gives honeycreepers time to bounce back. “The goal,” Farmer says, “is to get them off the endangered species list.”

On a Mission

Conservationists aren’t sure how long the recovery will take. Until then, Knox will continue doing drone drops. And Seidl will continue tracking mosquito numbers and honeycreeper health. That means hiking deep into the forest. “It’s pretty muddy,” Seidl says. “Mosquitoes love muddy, wet areas.”

FOREST VIEW Forests in Hawaii are teeming with wildlife, including many birds that are unique to the area.

IAN NELSON“Everyone is so committed and works so hard because we understand that it is our responsibility, our kuleana, to save these birds,” Farmer says. “And we can do that. We have the technology.”

Working Together

Birds, Not Mosquitoes is a partnership working to save endangered honeycreepers. It’s made up of 13 organizations and government agencies. “Everybody involved in conservation is part of this,” ABC’s Chris Farmer says.

The partnership’s drone drops take place near Haleakala National Park (above), on Maui. The Birds, Not Mosquitoes motto is I ola nā manu nahele. In English, it translates to “So the forest birds thrive.”

Correction, September 2: The original version of this story misstated two details. Drone drops take place near Haleakala National Park rather than inside it. And half a million mosquitoes are dropped each week by drones and helicopters combined.