Moving Mountains

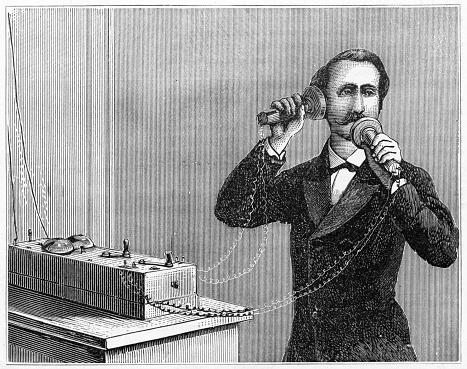

What do you imagine when you hear the word inventor? Many people picture Thomas Edison holding a lightbulb, or Alexander Graham Bell talking on the first telephone. But not all inventors are in our history books.

New inventions are being dreamed up and designed every day. Today’s inventors follow the same path that inventors did in the past: They identify a problem and create something to solve it. That can sometimes mean overcoming obstacles, but inventors always find a way.

TIME for Kids spoke to six young inventors who have done just that. They are improving the world and making history.

Two Helpful Apps

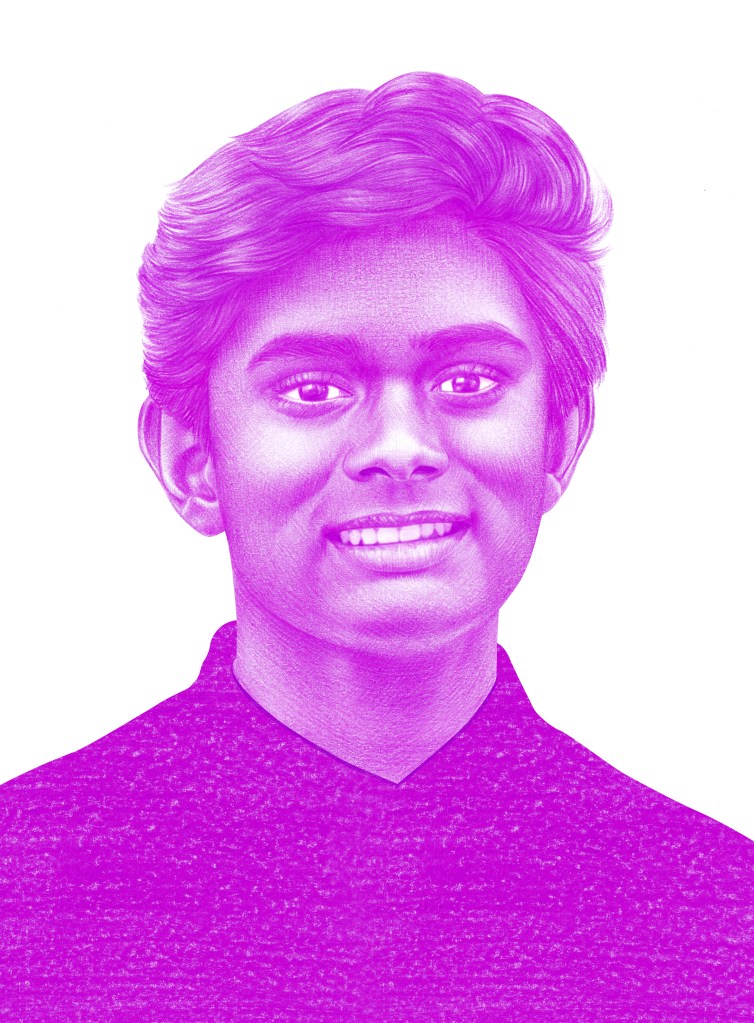

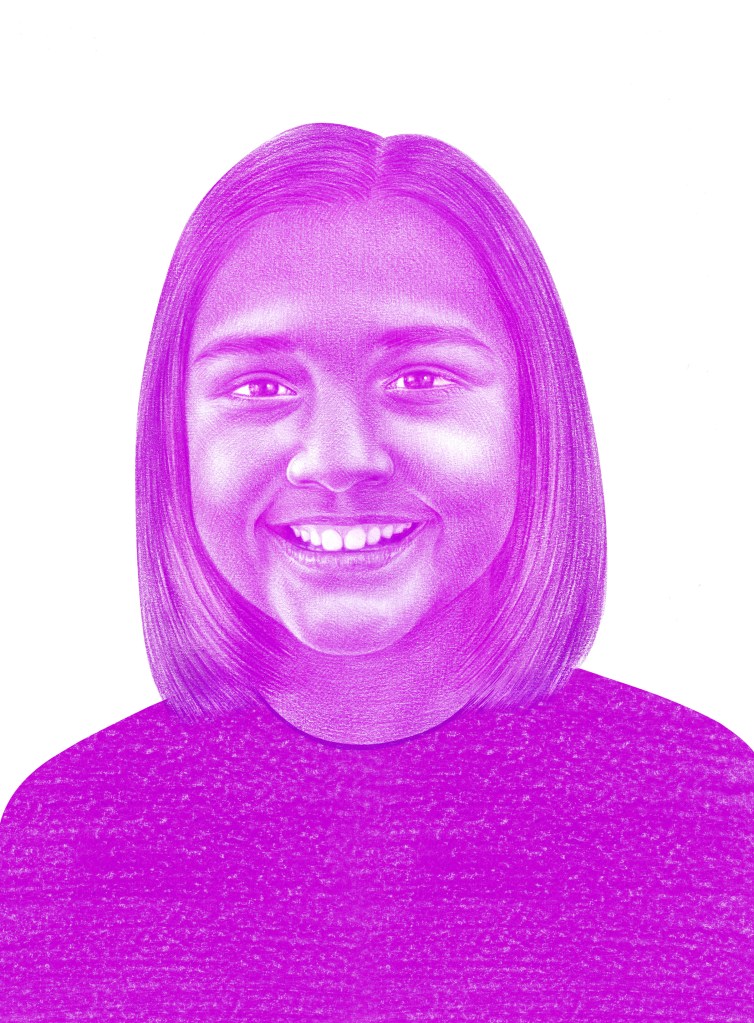

Neil Deshmukh’s introduction to artificial intelligence

artificial intelligence

THOSSAPHOL—GETTY IMAGES

the ability of machines to imitate human intelligence

(noun)

Artificial intelligence has made it possible to manufacture cars faster than ever before.

(AI) came three years ago. He wanted to keep his little brother out of his bedroom. That way, he could keep him away from his Nintendo DS. So Neil built a device. It could tell the difference between his brother’s face and Neil’s own. It would then lock or unlock the door. “In the very beginning, I was a tinkerer,” Neil told TFK.

THOSSAPHOL—GETTY IMAGES

the ability of machines to imitate human intelligence

(noun)

Artificial intelligence has made it possible to manufacture cars faster than ever before.

(AI) came three years ago. He wanted to keep his little brother out of his bedroom. That way, he could keep him away from his Nintendo DS. So Neil built a device. It could tell the difference between his brother’s face and Neil’s own. It would then lock or unlock the door. “In the very beginning, I was a tinkerer,” Neil told TFK.

Neil is now 17. He has created two apps. One of them is PlantumAI. It uses data to help farmers detect and diagnose

diagnose

JOSE LUIS PELAEZ INC./GETTY IMAGES

to identify a problem or disease

(verb)

Nate's doctor diagnosed him with the flu.

crop disease. The other is called VocalEyes. It describes photographs out loud. This helps people who are blind or who have low vision.

JOSE LUIS PELAEZ INC./GETTY IMAGES

to identify a problem or disease

(verb)

Nate's doctor diagnosed him with the flu.

crop disease. The other is called VocalEyes. It describes photographs out loud. This helps people who are blind or who have low vision.

Neil has a personal interest in the problems he’s chosen to tackle. In India, he saw the effect of crop disease on a village near where his parents were born. And his grandmother has low vision. He created VocalEyes with her in mind.

Neil lives in Pennsylvania. His work has won awards from companies such as Google, T-Mobile, and General Motors. —By Rebecca Katzman

A Better Cane

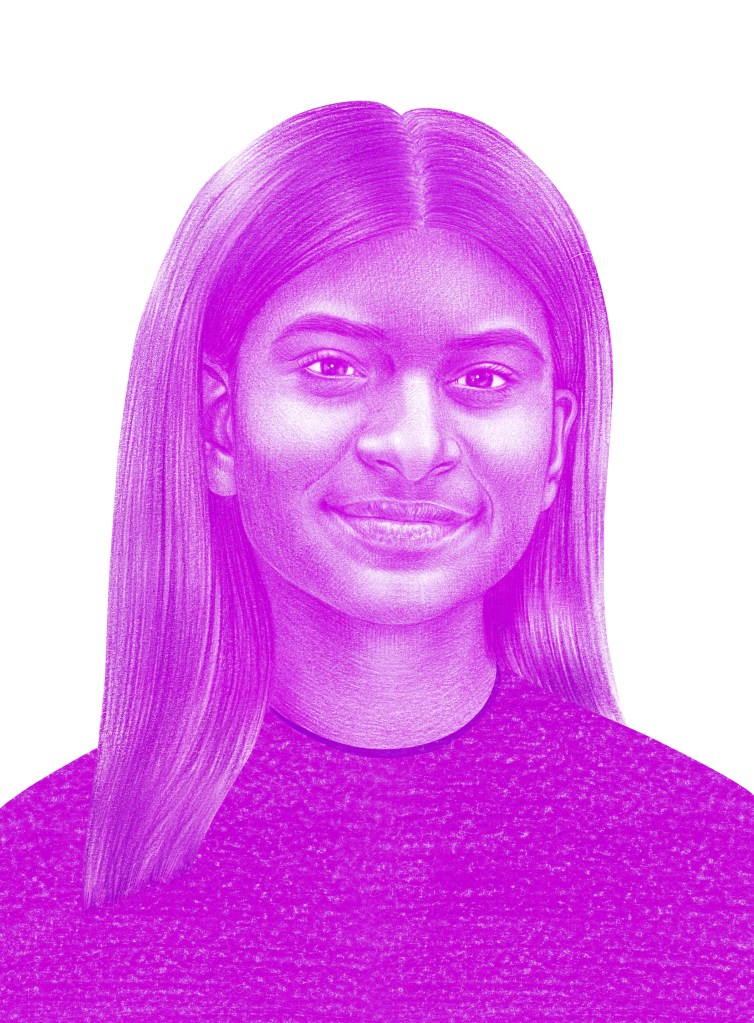

Riya Karumanchi met a woman who had trouble seeing. The woman used a white cane to get around. Riya was surprised that even with the cane, the woman struggled. She often bumped into objects that stood higher than knee level.

Riya assumed the cane came with cutting-edge technology. But she soon learned that wasn’t true. “It’s just a stick,” she says. “My initial thought was like, ‘What? How is nobody working on this?’”

Riya decided to work on it herself. At age 14, she engineered a device. It’s now called SmartCane. It uses sensors to spot obstacles and wet surfaces. It vibrates to alert the user to a dangerous situation. GPS navigation gives directions through vibrations and audio. An emergency button connects the user to first responders or loved ones.

Riya is now 16 and a high school student in Canada. She’s also the founder and CEO of the SmartCane company. She hopes to one day distribute the device through the Canadian National Institute for the Blind. —By Shay Maunz

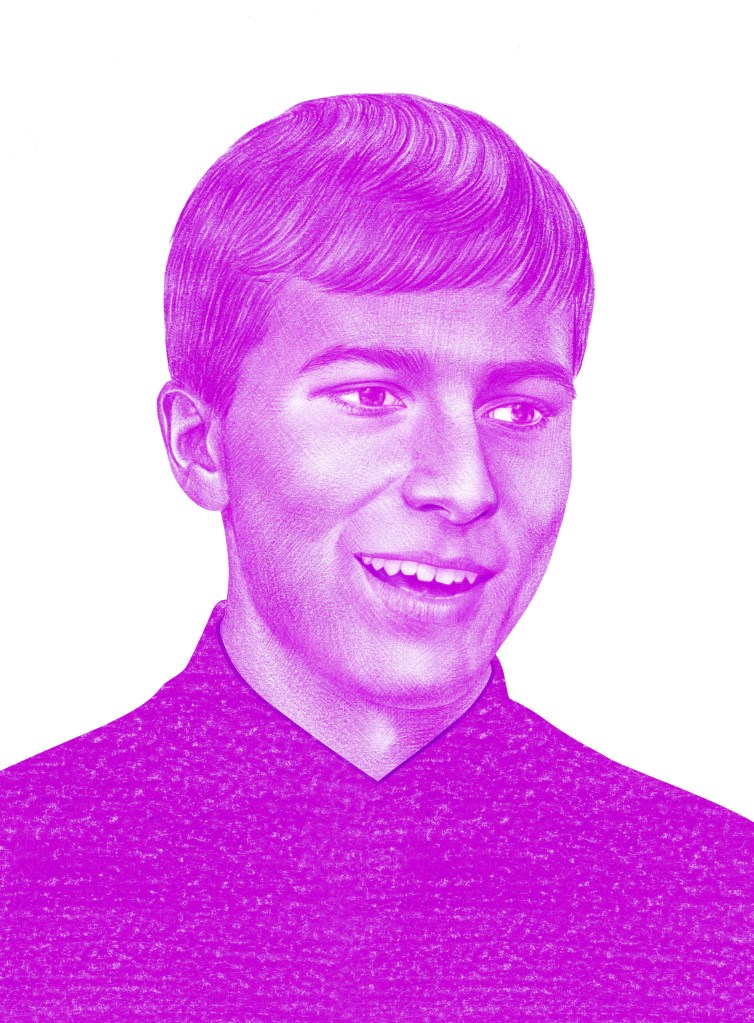

Braigo for the Blind

Shubham Banerjee loved Legos as a kid. But he didn’t use the classic plastic bricks to build castles or spaceships. He used them to make a product that could help people who are blind.

At age 12, Shubham needed an idea for a science fair. He was inspired by a flyer. It asked for donations for the blind. Shubham used the materials in his Lego Mindstorms EV3 robotics kit to create a Braille printer. It was much cheaper and lighter than any other Braille printer available.

A year later, Shubham and his parents founded a company. It’s called Braigo Labs Inc. Shubham made a new, metal version of the printer with help from investors

investor

HILL STREET STUDIOS/GETTY IMAGES

a person or group that contributes money

(noun)

Jordan's sister is an investor in his lawn-mowing business.

. That printer would cost $350 to buy. Other Braille printers can cost $2,000.

HILL STREET STUDIOS/GETTY IMAGES

a person or group that contributes money

(noun)

Jordan's sister is an investor in his lawn-mowing business.

. That printer would cost $350 to buy. Other Braille printers can cost $2,000.

Shubham is now 18. He’s studying business and engineering at the University of California, Berkeley. He has patents

patent

THEPALMER—GETTY IMAGES

the official right to make, use, or sell something

(noun)

Alexander Graham Bell received a patent for the design of the telephone in 1876.

for the Braigo printer. But he’s not sure what he’ll do with them. He says he might sell the company or “hold off until after my studies.” —By Ellen Nam

THEPALMER—GETTY IMAGES

the official right to make, use, or sell something

(noun)

Alexander Graham Bell received a patent for the design of the telephone in 1876.

for the Braigo printer. But he’s not sure what he’ll do with them. He says he might sell the company or “hold off until after my studies.” —By Ellen Nam

Passion for STEM

When she was 7, Gitanjali Rao invented a new kind of folding chair. Her design didn’t work. But that didn’t stop her from coming up with ideas.

Now 14, Gitanjali is an experienced inventor. In 2017, she won the 3M Young Scientist Challenge for Tethys. Tethys is a device that detects lead in drinking water. Gitanjali invented it after learning about the water crisis in Flint, Michigan. “I really wanted to go after this problem,” she says. “Each and every one of us has a right to know what’s in our water.”

Gitanjali’s new invention tackles cyberbullying. It’s an app called Kindly. Kindly spots and prevents mean online messages. “I’m going to throw a launch party at school,” says the ninth grader from Lone Tree, Colorado. “You need a party for everything.”

Gitanjali isn’t always in the lab. She also enjoys teaching. Her “innovation sessions” have attracted about 20,000 kids. “My mom has always told me that I’m good at explaining complicated concepts,” she says. “I want to work with students to find and develop their passion for STEM.” —By Jaime Joyce

Warming Up the Water

Xóchitl Guadalupe Cruz López grew up in a home that was often without hot water. So did many of the other residents of her hometown of San Cristóbal de las Casas. That’s in Chiapas, Mexico.

When she was 8, Xóchitl invented Warm Bath. It’s a solar-powered water heater made from recycled materials. “People here have to take baths with cold water. They have a lot of diseases,” she says, through an interpreter. “I wanted to do something.”

The Warm Bath prototype

prototype

SKYNESHER—GETTY IMAGES

a model

(noun)

Before construction began on the bridge, the architects built a prototype.

is made of objects that are easy to get. These include water bottles, a rubber hose, and plastic connectors. It costs about $30 to assemble.

SKYNESHER—GETTY IMAGES

a model

(noun)

Before construction began on the bridge, the architects built a prototype.

is made of objects that are easy to get. These include water bottles, a rubber hose, and plastic connectors. It costs about $30 to assemble.

Xóchitl, who’s now 11, created Warm Bath with the National Autonomous University of Mexico’s adopt-a-talent science program, PAUTA. In 2018, Xóchitl was the first child to receive the university’s Institute of Nuclear Sciences Recognition for Women award. When she found out, “the only thing I could think about was telling my parents and my brother,” she says. —By Constance Gibbs

Saving the Seas

Fionn Ferreira, 19, has always loved the sea. He grew up near the ocean, in Ireland. He often went kayaking and volunteered at beach cleanups. And Fionn has always loved science. His two passions met in 2017. That’s when he began looking for an eco-friendly way to remove microplastics from water.

The process Fionn developed won him the 2019 Google Science Fair. His method uses a magnetic liquid. It’s called ferrofluid. When added to water, ferrofluid sticks to microplastics. Magnets can then be used to remove the ferrofluid from the water. More than 85% of the microplastics are removed along with it, Fionn says.

Fionn built most of the tools he needed to test his method at home. There were hiccups along the way. “Some worked. Some didn’t. Some things blew up. Some caught fire,” he says. “The fuses of our house were constantly blowing!”

Fionn wants to continue his research. He also wants to inspire more kids to get involved in STEM. —By Karena Phan